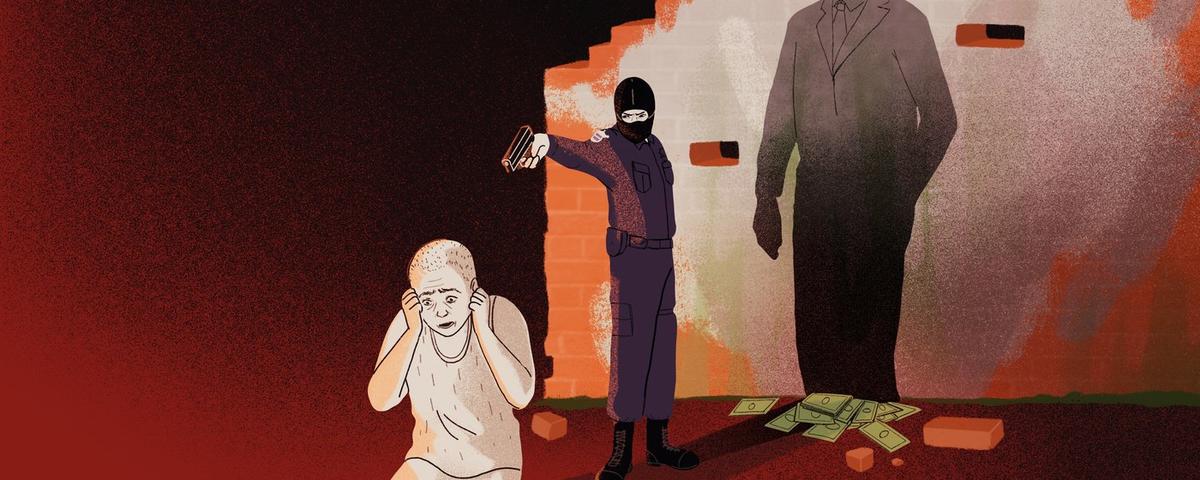

One afternoon in late February 2016, the mayor, eager to capture the media’s attention, summoned a group of trusted police officers to his office. He spoke to them bluntly. He wanted headlines; he wanted people talking about his municipality. And to achieve this, he gave them an order: They were to find a pair of gang members, decapitate them, and leave their heads at the entrance to the town. The mayor and the officers were no strangers. It wasn’t the first time he ordered them to kill, one of the agents recalls.

“The boss had asked for a scene to be staged that would be relevant and attract the attention of the media, and he had asked for some heads to be left at the entrance to the municipality of San Luis Talpa,” the officer, who claims to have received that assignment, recounted years later in court. That police officer became a protected witness for the Attorney General’s Office. He received an alias: Horus.

When Horus refers to “the boss,” he means Salvador Menéndez, mayor of San Luis Talpa since 2012 for the GANA party. Menéndez has been re-elected four times and is currently his party’s departmental director in La Paz. His last reelection was in 2024, and since then he has been one of the few mayors to survive the electoral reconfiguration imposed by Bukelismo in 2023, which drastically reduced the number of mayorships by four-fifths. He’s now mayor of La Paz Oeste, which comprises seven districts, including San Luis Talpa. Although he governs under the banner of GANA, the party that brought Bukele to the presidency in 2019, he has insisted in television interviews that Bukele “is my friend and I’m his ally.” Bukele, too, has had nothing but praise for the mayor in public.

Mayor Menéndez is a lucky man: Despite being mentioned more than 140 times in a trial against a death squad in late 2022, accused of ordering, financing, and paying rewards for 36 murders committed between 2015 and 2018, there is no arrest warrant against him. On Tuesday, October 28, at 4 p.m., Menéndez called El Faro to return requests for comment left with his municipal secretary. He said he was aware of the statements made by the key witness Horus, but assured that he had never been contacted by any authority in an official capacity.

As for Horus, he’s a former agent of the National Civil Police (PNC) stationed in different delegations in the center and east of the country. Although his name was kept completely confidential in the prosecutor’s investigations, El Faro has identified him: his name, his face, his police identification number, as well as his employment and criminal history from 2011 to date.

Horus was arrested on August 13, 2020, along with three of his fellow police officers from the death squad that operated in San Luis Talpa and its surroundings since 2015. The other officers were José Ricardo Campos, Carlos David Coreas Márquez, and José Amílcar Guidos. The witness refers to his group as Halcón 32, or “Falcon 32.” These four officers were taken into custody for the disappearance and murder on July 30, 2017, of Andrés Alexánder Guardado Ascencio, 18, and Kevin Alexander R., 17, as they were getting off a bus on their way home from school.

According to Horus’ confession, an informant at Rosario de la Paz Park identified the two young men as extortionists. The police followed them when they boarded a bus on Route 133 until they got off at a place known as “La Flecha.” Police ambushed them without witnesses, handcuffed them, and took them to a reed bed in the La Zambombera district of San Luis Talpa, where they laid them face down.

Horus describes the murder as follows: “They took each of their phones and [an officer with the call sign Chanta] grabbed one of them, putting a nylon string around his neck with two sticks tied to the ends, then pulled both ends until he suffocated the young man, putting his knee behind his neck to apply more pressure until the young man stopped moving and died. The other young man was shot in the back.”

Once in custody, Horus decided to cooperate with prosecutors and confessed to 75 cases, with a total of 97 victims murdered. In 23 of those cases, the witness mentioned Mayor Menéndez as the financier or mastermind behind the murder of 36 people, at least three of whom had no clear links to gangs. Horus’ testimony, deemed credible by the Attorney General’s Office, became one of its main pieces of evidence in getting the First Sentencing Court of Zacatecoluca to condemn his three accomplices in December 2022 to up to 180 years in prison for the crimes of forced disappearance and aggravated homicide.

In Horus’ 220-page confession, the he named the mayor 141 times: “Salvador Menéndez,” “Mayor Salvador Menéndez,” “Papá Chamba,” or “Patrón.” He says that, for at least four years, Mayor Menéndez paid for dozens of murders, operated as one of the group’s leaders, and facilitated illegal weapons or vehicle rentals with municipal funds. This information was obtained thanks to an email exchange on July 14, 2021, between Organized Crime Prosecutor Mirian Lorraine Alvarado Cerrato and analyst Jesús Alejandro Sandoval Hernández of the PNC’s Specialized Division Against Organized Crime (DECO), sharing the complete confession recorded by the Attorney General’s Office.

El Faro has a copy of the ruling issued by the Zacatecoluca sentencing court on April 17, 2023, in which the court separated Horus from the sentence, describing him as having provided “substantial evidence to support the entire accusation,” and indicating that his account was also credible to the three judges who convicted the police officers.

One chain link of the story, however, is broken: Although the court accepted Horus’ confession regarding the acts committed by his colleagues, it did not take into account the mayor as the mastermind behind 36 homicides or the other senior police officers identified by the witness. Almost three years have passed since the ruling, and prosecutors have not sought an arrest warrant for the mayor.

El Faro had access to the Horus’ full confession thanks to a massive leak of PNC emails known as the Guacamaya Leaks. The outlet conducted hundreds of searches in the database of more than two million emails, using keywords such as the real and code names of the witness, each of Horus’ colleagues, the mayor, the prosecutors assigned to the case, and the reference number, but was unable to determine why the mayor has not been charged. Attempts were also made to obtain a statement from the Attorney General’s Office, the Police, and the Supreme Court of Justice, but there was no response.

When consulted by El Faro, Fernando Meneses, who identified himself as the defense attorney for the convicted officers, recalled that, after the sentencing in December 2022, only one of them had been detained. He then said he would review the official document to provide more details. On Wednesday, October 29, we called the lawyer again, but he didn’t answer.

After the arrest and initial hearing against Horus and the other three officers in August 2020, the Specialized Court of Instruction “C” of San Salvador decreed total secrecy on the case. Nothing was known to the public until the conviction in 2022, when prosecutors released a bulletin with very brief information about the convicts, without mentioning that they were police officers.

El Faro also obtained 18 other documents, including minutes, intelligence reports, prosecutorial and judicial memos, witness transfer orders, and emails exchanged between police investigators and prosecutors working on the case. El Faro consulted with three PNC sources familiar with the case, who confirmed both the existence of Halcón 32 and Horus’ role in its operations.

The Order to Kill

The criminal investigation leading to the officers’ arrest, which included surveillance and wiretapping of those involved, was conducted between 2018 and 2020. The case went to court in August 2020, under the tenure of Attorney General Raúl Melara, who was investigating a series of corruption cases in Bukele’s administration. By the time the sentence was handed down two years later, in December 2022, Bukele was already in power and had made a series of political moves that transformed the judicial landscape in El Salvador: a sweeping purge of judges in August 2021; the ensuing installation of Bukele loyalists on the most influential courts in El Salvador; and the illegal replacement of Melara with the current top prosecutor, Rodolfo Delgado, on May 1, 2021.

The core allegations leading to the conviction of members of Halcón 32 date to earlier, between 2015 and 2018, before Bukele became president. That was why Horus informed prosecutors that in 2016, on Mayor Menéndez’s order, the police officers decapitated two MS-13 gang members known by the aliases Blazer and Burro, both 20 years old, and left their heads under the shade of a ceiba tree in the Telcualuya canton, three kilometers from the center of town. The scene made all the news programs. One of them was 4 Visión, the most-watched in El Salvador. The report shows the silhouettes of the two heads.

Two days later, according to Horus, he and another agent with the code name “Rocke,” also part of the extermination group, were summoned to Town Hall. Menéndez greeted them with a smile: “Congratulations, boys. Excellent work. That’s what I wanted,” Horus said, quoting the mayor. The witness asserts that the mayor ordered the murders with a peculiar intention: to position his municipality as one of the most violent and thus obtain more resources from FODES (Fund for Local Municipal Development), which the central government provided to city halls until October 2021.

“Most of the murders that were committed and paid for by Mayor Salvador Menéndez were carried out so that the mayor’s office would increase the FODES and thus have more money,” reads Horus’ confession. The document continues: “The informant does not know if the payment came from the mayor’s office or from the mayor’s personal funds, who is the owner of the Hotel Estero y Mar located in Zunganera in San Luis Talpa, department of La Paz.” El Faro reviewed the FODES budget allocations to the San Luis Talpa Mayor’s Office between 2012 and 2020 and did not notice a significant increase.

Horus points to a dozen other agents involved in the death squad, including two high-ranking officials. One is Chief Inspector Henry Barahona, then head of Plan Zafra in La Paz, tasked with ensuring security in the sugar cane mills in the area; and Deputy Chief Inspector José Hernán Peña Morales, then head of the San Vicente Investigations Department. These two police chiefs were also named in 2016 in another investigation into death squads by the Attorney General’s Office. The defense attorney Meneses, who also represented these senior police officers in fending off these allegations, said that both were acquitted and are now living outside the country.

According to Horus, the death squad did not only operate under the mayor’s directives. Some murders or acts of torture were committed by the group at the request of cattle ranchers or sugarcane businessmen in the area. And they were not only responsible for killing gang members. On two separate occasions, they attempted to kill a prosecutor and police investigator who were pursuing them. According to Horus, in August 2020, they even hired assassins to kill Father Ricardo Antonio Cortez, rector of the San Óscar Arnulfo Romero Seminary in Santiago de María, Usulután, while he was driving to the seminary. According to the witness, this murder was carried out in coordination with the San Vicente death squad at the request of a local drug trafficker known as “Chepón.”

In the call with the mayor on October 28, he dismissed Horus’ accusations as those of “a crazy person who wants to make himself look important.”

As for whether he had been notified by any authority of the accusation that he financed a death squad, he told El Faro: “Look, I don’t know anything about that. I simply know about the case, that they were caught somewhere else, not even in San Luis Talpa. They were people who knew each other in San Luis. As mayor, I help all state institutions. When the police, schools, public health need some kind of help and I had the possibility... Well, I even continue to help them to this day. We renovated the police station, the electrical system, maintained the vehicles, and a lot of things that at that time were very complicated... I understand that they [the arrested police officers] were doing things that were no longer allowed, and that they had to get someone else involved [in their accusations] so that the protected witness [agreement] could be... how can I put it, necessary, right? But I haven’t had any problems.”

The conversation continued: “So, what you’re saying is that you gave them money in order to help the police?”

“No, no, no. I didn't say I gave them money,” Menéndez responded.

“So who were you helping?”

“Everyone. I didn't say anyone in particular. I have helped, and I continue to help. But I didn’t give it to them.”

“Did you help them with cash or some other way?”

“In checks... or whatever. Or you buy the product. Do you understand me?”

“Because the key witness mentions that you gave them cash.”

“I didn't give them money. The key witness definitely wants to make himself interesting by linking the mayor of the municipality at that time, but that’s irrelevant.”

“Why do you think the key witness has accused you of financing a death squad?”

“Maybe because I’m well known, and these are people who want to cause trouble for any reason and will seize on anything to make themselves more credible.”

“This key witness appears to be quite credible, because the prosecution managed to convict three of his colleagues for up to 180 years thanks to his testimony. In other words, it seems that what the witness says is substantiated.”

“That’s not my concern, it’s a matter for the authorities, because I’m telling you what I know. Heh, heh, heh.”

“And do you know these police officers personally?”

“Well, I don’t know who you’re talking about, because there are so many who have been taken away and so many things have happened. I heard it on the news, but no-one pays attention to that anymore.”

“Have you been notified by the prosecutor’s office or the police or any other authority about this case and what the witness says?”

“No, no, never. What the witness says has no validity.”

“And how did you find out what the witness says?”

“These days, everyone knows everything, but not just him, a lot of people. Before, a lot of attention was paid to that, but now that all those bad guys are locked up, heh, heh, heh. There's no problem anymore. Do you understand me?”

“The witness mentions you and accuses you of ordering and financing 36 murders.”

“No, no, no! How could you believe that would happen? That’s impossible. That’s crazy. The witness is out of his mind, heh, heh, heh. I don’t have a problem with that.”

Shortly after, the mayor hung up.

Envelopes from the Mayor’s Office

According to Horus, his death squad began operating in early 2015. At that time, such organizations were spreading across El Salvador like an infection. They arose from the exhaustion of the police, caught in a seemingly endless war between the state and the gangs, and from the support of the highest-level authorities, such as then-Vice President Óscar Ortiz, who went so far as to publicly tell the police to “use their firearms” against gang members “without any fear of consequences.”

That year, following the breakdown of the truce between the FMLN government and the gangs, and the return of criminal leaders to maximum-security prisons, was the most violent of the entire postwar period, with 106 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants. Gang members killed more than 90 police officers and 60 soldiers, mostly while they were off duty, and the security forces responded with extrajudicial executions that they presented as confrontations with criminals.

Horus’ group consisted of four low-ranking PNC officers stationed at the San Luis Talpa police station, whom he identifies by the call signs Rocke, Vegueta, Chiquita, and himself. The name “Halcón 32” is apparently in reference to the number of their police unit.

This cell did not operate under the exclusive orders of the mayor, but in coordination with the police station chief in San Luis Talpa and the head of the San Vicente departmental delegation. In other words, according to Horus, they operated under the direction of two senior officers of the corporation. In some cases, according to the witness and police intelligence documents in the possession of El Faro, the coordination extended beyond their assigned area and they assisted other death squads in the departments of Ahuachapán, Usulután, and San Miguel.

In his confession, Horus offers detailed accounts of 75 cases in which they killed, tortured, and disappeared a total of 97 victims. The modus operandi was the same in all cases: They identified their victims, arrived at their location pretending to be conducting a police operation, and executed them, then collected their reward paid by the mayor, local businessmen, and sugar producers in the area. In some cases, Horus also claims they received payments from a local drug trafficker whom he identifies only as “Chepón,” who allegedly had ties to a drug cartel about which he gives no further details.

Regarding the mayor’s payments for the 36 murders, Horus claims that, in some cases, the mayor directly identified the victims by name, alias, and even location. In others, they selected the gang member, killed him, and then went to collect their reward from the mayor.

The police officers approached the victims in uniform, carrying issued weapons and riding in patrol cars. Under the pretense of a police operation, they took them to unpopulated areas, such as the abundant sugar cane fields in the area, to kill them, sometimes with their official weapons, sometimes with illegal weapons or even machetes.

The first of the 75 crimes described by the witness was a murder for which he says the mayor paid them $1,000. This occurred on March 16, 2015, at a ranch on El Pimental Beach, in the jurisdiction of San Luis Talpa. That day, Halcón 32 received details from an informant about the exact location of an MS-13 gang member known by the alias “Playa.” The informant claimed that Playa was moving around an abandoned ranch at dawn. The witness said that, days earlier, Inspector Barahona, head of Plan Zafra at the time, had explicitly asked them to “kill gang members by simulating an exchange of gunfire and show off the work that Plan Zafra was doing in the area to win sympathy from the sugar growers, who would send them extra pay for a job well done.”

The Halcón 32 team arrived in a patrol car around 3 a.m. on March 16, fully armed and in uniform, at the shack where they knew the gang member was sleeping. They entered quietly and spotted him. “They took up positions to attack the victim using a distance technique, covering a perimeter of twenty meters, where the subject could run, so when the victim reached their location, they pointed their guns at him. When they had him in the middle, they said, ‘Stop, police! Don’t run.’ And the victim raised his hands and knelt down,” according to the confession written in a prosecutor's report.

As in most of the cases confessed by Horus, after subduing their victim, the agents handcuffed him and shot him from a distance of approximately five meters. They then altered the scene to make it look like a confrontation. “Then the speaker collects several shell casings that were visible, leaving only those necessary to make it look like there had been an exchange of gunfire, and Vegueta removes the handcuffs,” the document says.

El Salvador's Police Kill and Lie Again

This case, and nine others in which the witness points to the mayor, have been corroborated by El Faro through news articles published by local media, which confirm that those people died on those dates. An article in La Prensa Gráfica, published on March 17 of that year, with the headline “The previous weekend was the most violent of the year,” reports Playa’s murder: “A gang member died in this private ranch on El Pimental beach after confronting members of the PNC who were responding to a report of gang members gathering there.”

According to Horus, sometimes it was not necessary for the mayor to assign the victim: They killed and the mayor rewarded them. On the same night they left the two heads at the entrance to the municipality in February 2016, the team killed two other men, a father and son, accused of being gang members, taking them from their homes and leaving them at the entrance to a cane field, about three kilometers from where they left the heads. Those two bodies were also reported by 4 Visión the following day. According to the article, the victims were José María Aguilar, 55, and José Antonio Aguilar, 30.

Horus’ account is so detailed that it includes how one of the agents pulled the younger Aguilar’s shirt up over his head before shooting him. He left him blindfolded, handcuffed, and kneeling while he shot him. In the 4 Visión news report, an officer guarding the scene describes the same thing: “There’s one with his head covered; his shirt was kind of taken off and left covering his head.”

According to Horus, after leaving the heads, the officers found MS-13 graffiti. One of them took a red spray can they had in the patrol car, crossed it out, and added a message: “Time’s running out, you pieces of shit.” The image of the message also appears in the article published by 4 Visión.

According to Horus’ account, the mayor always paid after the murders, and the fee was $1,000 per execution. He says the money was delivered by the mayor in white envelopes with the logo of the Municipal Mayor’s Office of San Luis Talpa, sometimes at his municipal office and sometimes at the Hotel Estero y Mar office. In most cases, Horus claims that he himself went to receive the payment from Menéndez. He estimates that the mayor handed over a total of $27,500 to the death squad for the murder of 36 people between 2015 and 2018.

In all cases where the witness went in person to receive the money, he describes the event in a similar way: “At the mayor’s office, they were greeted at the door by the mayor’s security guard, who directed them to the office of Mayor Salvador Menéndez. Upon entering, the witness observed Salvador Menéndez at his desk, who told the four of them to sit down. So Rocke and the witness sat in the two chairs in front of the desk, while Vegueta and Beltrán sat in armchairs at the back of the office.”

In all cases where the mayor handed over the money personally, the witness describes seeing him handle large amounts of cash without knowing whether they were public funds or the mayor’s own money. “Then Mayor Salvador Menéndez opened one of the desk drawers, took out a wad of cash, and gave each of them two hundred U.S. dollars, for a total of eight hundred dollars. and then gave two hundred dollars to Rocke and told him that he only had twenty-dollar bills, so he should divide them up so that everyone would have two hundred and fifty dollars,” the confession states.

The Estero y Mar beach ranch is a well-known tourist spot in El Salvador, famous for its beautiful sunsets. Although El Faro could not corroborate that it is owned by the mayor, the witness Horus makes this assertion throughout his account. On Tuesday, October 28, El Faro called the hotel. The secretary, identified as Esmeralda Valencia, said she could take messages for the mayor even though he “hardly ever stays at the hotel” and assured that the place is his property.

Horus also accuses the mayor of providing the death squad with vehicles and illegal weapons to carry out killings. For example, in the case identified by the Attorney General’s Office as “Caso Tomate,” which occurred in early January 2016 and involved the murder of two alleged MS-13 gang members, Halcón 32 traveled in a rented orange sedan. After the murders, Horus claims that they received $1,000 in a white envelope with the logo of the San Luis Talpa Mayor’s Office and that his partner Rocke told him that the municipality would pay for the vehicle rental.

In the case identified by the Attorney General’s Office as “Caso Huevitos,” which occurred in late September 2016, Horus recounts that after the murder of two alleged MS-13 gang members inside a cane field near the place known as Campamento San Luis Talpa, Halcón 32 agents staged a scene to make it look like a confrontation. The agents placed two shotguns, one next to each dead gang member. According to Horus, while other agents were processing the scene, “the witness heard when [an agent with the call sign Pirata] placed a call to the mayor and told the Halcón 32 agents that Papá Chamba, referring to Salvador Menéndez, sent word that it was excellent work and that those shotguns were the last ones he had where the peludo [nickname for “hairy guy”] was.”

In three of the 23 cases implicating Menéndez as mastermind or financier, the witness recounts how the mayor instructed them to kill for reasons unrelated to the intended increase in FODES funding.

In the cases referred to by prosecutors as “Miradores” and “Quema de Casa,” Horus claims that the mayor ordered the burning of two houses next to his Hotel Estero y Mar because he wanted to build lookout spots in that area and the residents, including a leader of the FMLN party, did not want to leave their land despite having been warned by the municipality. In both cases, the police, in uniform and with service weapons, spread gasoline around the houses, with adults and children still inside, and threatened residents to leave. In another case called “Caso Patota,” the witness claims that the mayor ordered the killing of a gang member with that alias “because Patotas was often a nuisance at the beach where he has the hotel, and he paid a thousand dollars to carry out the mission.”

Of those 23 cases, 13 had one victim, nine had two victims, and one had five victims.

Although in most cases the murders took place within San Luis Talpa, this latter killing of five people occurred in the canton of Valle Nuevo, in the neighboring municipality of Olocuilta. The mayor allegedly paid them out, but complained about jurisdiction. “That same day, at approximately 5:00 p.m., Pirata arrived in the patrol car at the Amatecampo rest house and gave Rocke one thousand U.S. dollars, which was an incentive for what they had done, on behalf of Mayor Salvador Menéndez, but he sent word that next time they should leave them in San Luis Talpa because Olocuilta was of no use to him for controlling the mayor’s office," the confession states.

The first part of the massacre took place in the Valle Nuevo canton and is identified in the confession as “Caso Valle Nuevo.” According to Horus, the operation began as midnight approached on December 31, after they received information about a group of gang members drinking alcohol in a house. The Halcón 32 team prepared and set out for the location. When they found a group of alleged gang members, the agents fired their rifles, injuring four and finishing them off on the ground. Upon searching the area, the agents realized that a fifth gang member was hiding under a taxi and killed him, too.

After staging the scene to make it look like a confrontation, the agents learned that two more young men were hiding in a nearby house and identified them as gang members. They took them out and brought them to a garbage dump in Olocuilta, where they shot them, thinking they had killed them, but one of them survived and was taken to the hospital in Ahuachapán. Although they are also mentioned in “Caso Valle Nuevo,” prosecutors separated the case of the latter two young men as “Valle Nuevo Two.”

According to the witness, the quintuple murder and subsequent assassination each brought a reward. “On January 1, 2016, they committed a quintuple homicide in the Valle Nuevo Canton, jurisdiction of Olocuilta, department of La Paz, in which they simulated an exchange of gunfire to get away with the quintuple homicide, and for that act, Mayor Salvador Menéndez paid them a thousand dollars as an incentive,” says the confession.

The massacre was reported by several national media outlets, including La Prensa Gráfica, which ran the headline “First day of the year with a massacre and a confrontation.” The press report gave the authorities’ version of events: the first five had been killed by an unknown group and one more in a confrontation between gang members and police at the Olocuilta garbage dump.

Prosecutor and Priest

The last case that witness Horus points to as having been ordered by the mayor occurred in January 2018. From then on, his account mentions other actors as instigators or financiers, and even some murders committed on their own initiative.

In mid-2016, almost a year after El Faro published a lengthy investigation showing that police had massacred eight people, including one who was not even a gang member, on a plantation called San Blas, the Attorney General’s Office, then headed by Douglas Menéndez, launched a series of prosecutions against death squads in the eastern part of the country. Most of these investigations ended in pyrrhic convictions for a small group of low-level police officers. Others were left in impunity.

In March 2018, in the court of San Pedro Masahuat, a municipality neighboring San Luis Talpa, the judge held a preliminary hearing against several police officers accused of belonging to a death squad, including Horus. According to the witness, the members of the group planned the murder of the prosecutor who had charged them with quadruple homicide. This case became known as “Caso Miraflores.” This one had nothing to do with the mayor, according to the witness.

On the morning of the hearing, the witness, his colleagues, and other members of the extended circle of the death squad met to devise a plan: “Rocke said, ‘this maistro [old guy] is really pissing us off,’ referring to the prosecutor handling the case. He went on to say that the prosecutor was very good and that there was a fear that they would be detained or even convicted, and they told the speaker that those present had decided to kill him.”

Two politically prominent figures from El Salvador attended the hearing to show their support for the police officers: Marvin Reyes, union president of the Police Workers’ Movement, and Osiris Luna, then a deputy for GANA and, since 2019, the director of prisons and Vice Minister of Security and Justice in the Bukele administration. According to the witness, after the preliminary hearing, all those accused were released. Despite the insistence of some members, they agreed to spare the prosecutor’s life.

One of the most emblematic recent cases highlighted by Horus is the murder of priest Ricardo Antonio Cortez, rector of the San Óscar Arnulfo Romero seminary in Santiago de María, Usulután, and parish priest of San Francisco Chinameca, La Paz. The murder took place on August 7, 2020.

According to Horus, the Halcón 32 extermination cell did not act alone in the priest’s murder. It coordinated with a police team from San Vicente and another coordinated by Inspector Peña Morales. According to the witness, four preliminary meetings were held, with the last one to collect payment for the execution. This murder, according to Horus, was ordered by a local drug trafficker known as “Chepón,” who had previously ordered other murders.

At one of the preliminary meetings, Horus says that Inspector Peña Morales assured them that the victim was a local cattle rancher named Bravo, whom Chepón wanted to eliminate. According to the witness, Chepón and Peña Morales explained that they intended to set up a vehicle parts store and that, to finance it, they had to execute that person in order to collect a reward of $10,000. In the following days, Halcón 32 allied with the San Vicente cell, allegedly led by Peña Morales, which included agents with the call signs Comando Rosario, Chilo, and Campos. They planned to set up a roadblock to stop the victim and wait for instructions from Peña Morales and Chepón.

On August 7, around kilometer 80 of the Litoral Highway, which runs from Zacatecoluca to Usulután, the uniformed agents —among them Horus— stopped a blue Toyota Hilux, according to the instructions they had received, and asked the priest to get out of the vehicle.

“Upon observing him closely, Chepón nods affirmatively to Comando Rosario, who shoots the victim once in the head with the victim’s own weapon as he stands on the road, watching the victim fall at Comando Rosario’s feet,” Horus’ confession states. The next day, the priest’s death was in the news. In an article in La Prensa Gráfica, an agent notes that the priest was found with a single gunshot wound behind his left ear and a bullet casing at the scene.

After Comando Rosario shot the priest, Horus “ordered Chilo and Campos to lift the body and move it away, placing it on the hill; he then looked inside the vehicle and saw that there was a laptop, a white shirt hanging on a hook, a carton of eggs, and other items of clothing,” according to the confession.

The murder of Father Cortez shocked the Catholic Church. The Episcopal Conference of El Salvador, the highest authority in the country, demanded justice. To date, the priest’s murder remains unpunished, despite the fact that prosecutors have a witness who identified the alleged killers.

For this murder like the others, the death squad received its reward two days later — this time at the Zacatecoluca police station. “The interviewee observes that Peña Morales was with Chanta in a white Nissan vehicle owned by Gallo más Gallo, and Peña tells the speaker not to get caught up in trivialities and tries to give him five hundred U.S. dollars for the murder of the priest, to which the speaker replies that he does not want the money, as he already has everything arranged to go to Mexico.”

My Friend, the President

The relationship between the mayor of San Luis Talpa, Salvador Menéndez, and Nayib Bukele dates back to at least 2013, when Bukele was mayor of Nuevo Cuscatlán and Menéndez had been in office for a year. Their first public encounter stemmed from an environmental crisis caused by lead contamination from the abandoned Baterías Record factory in the Sitio del Niño canton. Menéndez denounced the state’s neglect and harm to inhabitants’ health. Bukele came to his defense on Twitter: “The @AlcaldeMenendez of San Luis Talpa is crying out for help. He is not from my party, but his cause is just. We must support #AcciónEnSanLuisTalpaYA [Action in San Luis Talpa NOW].”

According to Bukele’s tweets, the now-president did not know Menéndez before the environmental crisis, but they began to forge a friendship that soon became public. “I met the mayor of San Luis Talpa. He’s not from my party, but I found him to be a good man committed to his people,” Bukele tweeted on July 3, 2013.

A little over a month earlier, on May 23, Bukele had initiated public interaction following a television interview in which Menéndez denounced a kidney failure crisis in his municipality, allegedly caused by lead contamination. “Greetings to the mayor of San Luis Talpa. I didn’t know you, but after seeing this interview, let me tell you that you have earned my respect,” Bukele wrote.

After Bukele’s public pressure, the sympathy between the two grew in the public eye. On November 20, 2013, Mayor Menéndez shared on Twitter an interview he had given to the website El Blog: “@nayibbukele should be our next president.” At the time, Bukele’s immediate goal was not to run for president, but for mayor of San Salvador, a position he attained in May 2015. Bukele responded: “Thank you, Mayor, for your words. I won’t be president, but you can count on me in the fight for your people.”

Later, on April 3, 2014, Menéndez posted a photo of the two of them in what appears to be the terrace of a café. “It’s always a pleasure to talk and learn from you, Mayor @nayibbukele,” he wrote. Bukele replied, “Thank you, Mayor, I’m the one taking notes.”

Years later, in 2019, when Bukele registered at the last minute with GANA to run for president, he chose San Luis Talpa to hold one of the few public events of his campaign, which was almost entirely on social media. On January 7, Bukele was greeted at the central park by the mayor and leaders of GANA. At the time, Menéndez told El Faro that he himself had financed part of the rally, paying for transportation to bring supporters from surrounding municipalities such as San Rafael Obrajuelo, San Luis La Herradura, Santiago Nonualco, and Rosario de La Paz. “It’s my own money, not from Town Hall,” he said.

By the time Menéndez financed the rally, the mayor had already ordered at least 36 murders by the Halcón 32 death squad, according to Horus.

After Bukele became president in 2019 and broke with GANA, Menéndez continued to call him a friend and ally.

On June 14, 2023, the Bukele-controlled Legislative Assembly reduced the number of municipalities in the country from 262 to 44. This had two main effects: on the one hand, it increased the concentration of power, something Bukele has been doing since he became president; on the other hand, by drastically reducing the number of mayorships, it made it more difficult for candidates to win.

During the campaign, most mayors and deputies from the ruling party Nuevas Ideas rode Bukele’s coattails, proposing that they would provide governability to the president. Menéndez ran for his fifth term with a campaign slogan that he still keeps as his banner on X: “GANA in a new alliance with President Nayib Bukele.”

On March 3, 2024, Menéndez won re-election in San Luis Talpa, newly redistricted as La Paz Oeste with an expanded seven districts. Nine days after winning, in a television interview on Frente a Frente, Menéndez said that the reduction in the number of mayors would give the central government more control. “In previous years, we’ve done a poor job, we’ve spent the money, we’ve misappropriated it many times, in a series of situations that are detrimental to the people,” he said.

Interviewer Moisés Urbina asked about comments on social media that he had won by proximity to Bukele. Menéndez replied: “I’ve been friends with President Bukele for many years. I love and respect him very much, and admire him for being a brilliant man, and if people believe that I clung to him, then I’m glad. Here I am, and I’m sure that President Bukele will not abandon me, at least not during these three years that the people have given me to govern.”

At the end of the call between El Faro and Mayor Menéndez on October 28, Menéndez avoided talking about Bukele.

“Those are personal matters,” he said. A phone rang in the background, stopping abruptly. The mayor continued: “I really don’t want to talk about this anymore. I answered you honestly, with the truth. I didn’t imagine you were going to come out with this. So there you have it, my friend, I’m going to leave you now because I have an important call to take.” He hung up.

Bryan Avelar is a Salvadoran journalist specializing in coverage of gangs, migration, and organized crime. He has published in The New York Times, El País, Insight Crime, El Faro, and Revista Factum, among others. Winner of the Ortega y Gasset Award (2024), Gabo Award (2025), and Ondas Award (2025).